“Speech is power: speech is to persuade, to convert, to compel.” (Emerson)

In the June issue of Nature Neuroscience, the investigator, Josef Rauschecker, PhD, and his co-author, Sophie Scott, PhD, a neuroscientist at University College, London, say that both human and non-human primate studies have confirmed that speech, one important facet of language, is processed in the brain along two parallel pathways, each of which run from lower- to higher-functioning neural regions.

These pathways are dubbed the 'what' and 'where' streams and are roughly analogous to how the brain processes sight, but are located in different regions, says Rauschecker, a professor in the department of physiology and biophysics and a member of the Georgetown Institute for Cognitive and Computational Sciences.

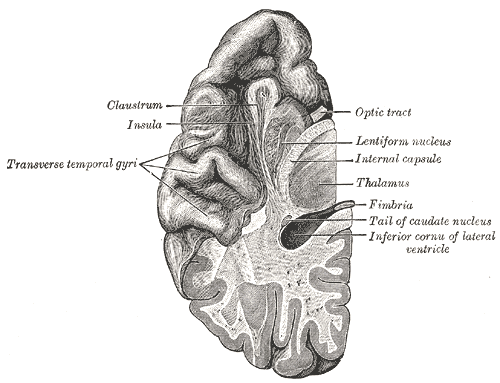

Both pathways begin with the processing of signals in the auditory cortex, located inside a deep fissure on the side of the brain underneath the temples - the so-called "temporal lobe."

Information processed by the "what" pathway then flows forward along the outside of the temporal lobe, and the job of that pathway is to recognize complex auditory signals, which include communication sounds and their meaning (semantics).

The "where" pathway is mostly in the parietal lobe, above the temporal lobe, and it processes spatial aspects of a sound - its location and its motion in space - but is also involved in providing feedback during the act of speaking.

What is so interesting to Rauschecker is that although speech and language are considered to be uniquely human abilities, the emerging picture of brain processing of language suggests "in evolution, language must have emerged from neural mechanisms at least partially available in animals," he says.

"Speech, or the early process of language, is well modeled by animal communication systems, and these studies now demonstrate that primate auditory cortex, across species, displays the same patterns of hierarchical structure, topographic mapping, and streams of functional processing," Rauschecker says.

"There appears to be a conservation of certain processing pathways through evolution in humans and nonhuman primates."

"But mostly, we are fascinated by the fact that humans can make such exquisite sense of the slight variation in sound waves that reach our ears, and only lately have we been able to model how the brain knows how to attach meaning to these sounds in terms of communication."

--

Source: Scientists Reaching Consensus On How Brain Processes Speech

No comments:

Post a Comment